In my last post I talked about being forced to drop Sync.com as my cloud file synchronisation solution when I moved to Linux because Sync doesn’t have a native Linux client. (I now use the excellent, cross-platform Tresorit, fyi.)

You know what I didn’t have to drop when I moved to Linux because it does have an excellent Linux client? Joplin, my open-source, cloud-synchronised note taking solution.

The tools I use to stay in sync

These are all the tools I use to keep my thoughts, notes, lists, tasks, and bookmarks synchronised across my four primary personal devices (desktop computer, laptop computer, tablet, and smartphone) and, when needed, my two work devices (laptop computer and work smartphone).

Long, secure notes: Joplin

The primary tool I use to capture all my thinking, planning, researching, documenting, and cataloguing is Joplin (created and maintained by London-based developer Laurent Cozic).

I love Joplin because:

it’s free (though I support its development via a Patreon membership),

it’s open source (at least the desktop client is),

it’s cross-platform (yay Linux client!),

it lets you use a range of back-end cloud storage options to sync your notes (otherwise at heart it’s an offline-first note-taking app),

it lets you use Markdown to structure you text, and

it provides end-to-end encryption (E2EE) for all you notes.

Unlike a lot of other, and perhaps, more popular note-taking tools – the commercial kind that you have to pay for – Joplin isn’t trying to be the everything-tool for everyone. It does a few things, and it does those well. It is relatively uncomplicated and its apps are all lightweight.

I especially like that you can choose among a bunch of cloud storage options to store and sync your notes in the back end. I already have 1TB of space on OneDrive (through our Microsoft 365 Family subscription) so I use that to sync my notes. And since all my notes are end-to-end encrypted, I have no security or privacy concerns with using OneDrive’s cloud storage for this purpose.

(Joplin has since launched Joplin Cloud to provide its own back-end cloud note-syncing functionality. This back-end synchronisation server is the only part of Joplin that’s not open-source.)

Short, casual notes: Google Keep

I use Google Keep because it consistently has the fastest and most reliable note synchronisation. Also, its lightweight apps works brilliantly on Android, iOS, and the web.

Content in Keep is (surprisingly for Google) private, but I don’t save anything secret here because your notes can still be subpoenaed.

Kanban board: KanbanFlow

KanbanFlow is a simple, lightweight kanban board / project management tool from CodeKick out of Gothenburg, Sweden.

I don’t use this for project management though, I use it to maintain the lists of books, TV series, and movies I want to watch next. (I’ve written about this use case before, if you’re interested.)

If I did need a project management tool though, I’d switch to the paid version of KanbanFlow.

(Trello used to be my preferred kanban tool but its developers kept adding features I didn’t want or need, to the point that it was no longer a fun, easy, lightweight web or smartphone app to use. It got even more complicated to use after Atlassian purchased it and added it to their suite of team-oriented products.)

Shopping and other lists: Microsoft To Do

Nadia and I have tried a bunch of list-making apps over the years, but Microsoft’s To Do is the simplest, most convenient, and most reliable of the lot.

(Our Family subscription to Microsoft 365 is why this app was even an option for us in the first place, by the way.)

Bookmarks and read-later links: Pinboard

Pinboard is an incredibly simple, very fast, and super efficient, web-based bookmarking tool that lets you bookmark webpages and, importantly, tag them for easy indexing.

It also has an ‘unread’ tag that lets you use this as a place to store all your read-later links. My read-later app of choice used to be the now-defunct Pocket, but I switched to Pinboard a few years ago and never looked back.

(For completeness’ sake I should mention that I use Firefox and Vivaldi browser accounts to sync my day-to-day web bookmarks, browsing history, and browser settings.)

Passwords and TOTP: Bitwarden, Aegis Authenticator

I use the amazing, open-source Bitwarden to generate, store, and sync all my passwords and the fantastic, open-source Aegis Authenticator to generate all my time-based one-time passcodes (TOTP).

Why sync notes in the first place?

Growing up I captured my notes, thoughts, and shopping lists using paper notebooks, notepads, and lined notepaper that I stored and organised in ring binders (complete with dividers and colour-coded tabs).

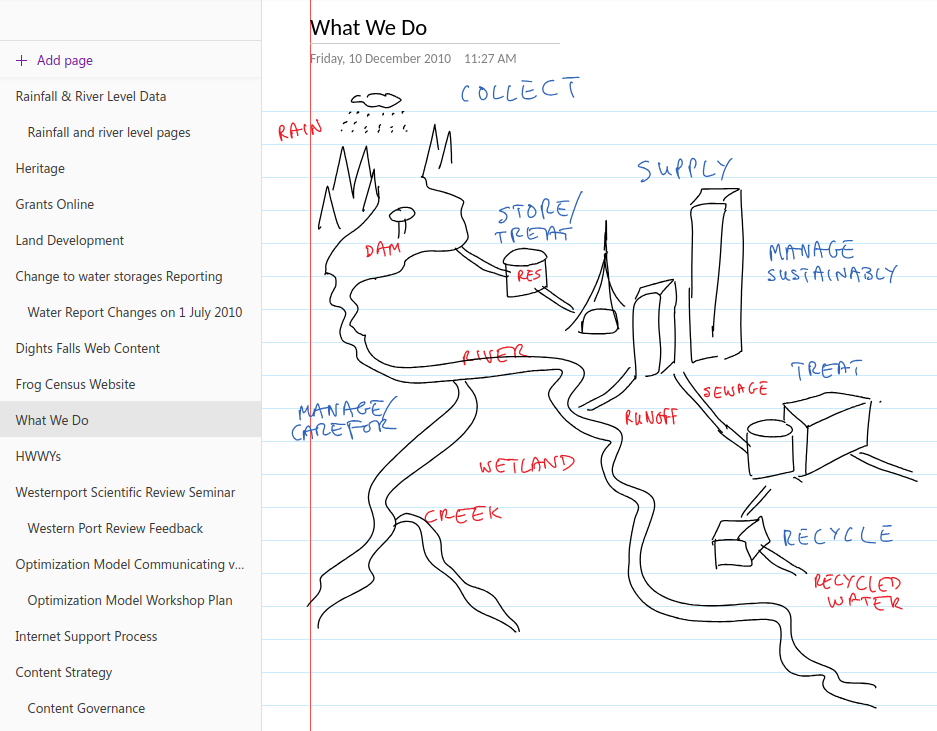

Once I got a job and stopped needing to carry ring binders around, I took notes on nicer notebooks from Moleskine, Leuchtturm 1917, and Field Notes. These paper-based methods saw me through my bachelors degree, masters degree, several jobs, and even my bullet journaling era (like in the scanned page above).

These days its easier to carry only a smartphone in your pocket instead of also carrying a notepad and pen with you everywhere. I’m more digital than most people, so it was inevitable that my note-taking would go all-digital sooner rather than later.

That switch happened in 2010 when I got an Evernote account and moved all my note-taking online. I loved Evernote because I could easily organise, index, and search through my notes. I could also access all of my notes, all of the time, regardless of where I was and which digital device I happened to be using.

The rise and fall of Evernote

Evernote was great in those early days so I signed up to a Premium subscription in 2012. I loved using it for everything from note taking, to cataloguing recipes, to saving blog posts and newspaper articles for later reading,

But as its desktop, web, and smartphone apps became increasingly complicated, bloated, and slow, the less I wanted to use it.

Evernote eventually went down the enshittification route so I dropped it altogether, as did many others.

Short foray into OneNote and Google Docs

I tried Microsoft’s OneNote for a while because I’d bought a tablet PC and OneNote let me take hand-written notes (using the stylus) on its desktop version – like in the screenshot below.

However OneNote didn’t have cloud sync to begin with, and when that functionality did arrive, is wasn’t particularly good, so I stopped using this too. (It was also always slower than Evernote and too unstructured for my liking anyway.)

For a while I also explored taking all my notes in Google Docs and storing everything in a specific note-taking folder. This worked fine for some longer, more complicated notes, but it was never convenient for everything. Google Docs is optimised for document writing, not simple note taking, after all.

Settling down with Joplin and, at work, plain text files

Eventually I found Joplin, fell in love with it, and then migrated all my personal notes over in January 2020. I haven’t found, or even needed to look for, a better alternative since.

Funnily enough, a version of that notes-in-Google-Docs idea is what I ended up adopting for note-taking at work. For several years now I’ve been taking all my work notes in plain old text files that I edit using Notepad++ and store in my work OneDrive.

I use a combination of four text files:

tasks.txt, in which I maintain a list of daily, weekly, quarterly, and yearly tasks for myself and my team

coordination.txt, in which I jot down my meeting notes

projects.txt, in which I write notes about the large projects I’m working on

people.txt, into which I take notes during the one-on-one meetings I have with my manager and my direct reports

Every Monday I create new versions of those text files (with Monday’s date in the filename), deleting notes from previous weeks that I no longer need for my current work. This way my active files remain short and focused, and it’s still pretty easy for me to search through earlier weeks’ files if I need to find something older.

(I used to use Trello at work for tracking personal tasks, coordinating team tasks, and for managing team projects, but our IT team “rationalised” our suite of tools and now we’re stuck with Microsoft Planner which is…not great.)

Investigating alternatives (or not)

I said I haven’t felt the need to look for Joplin alternatives, and that’s true, but I did play around with Standard Notes for a little while. This is a paid service that I thought might be a good, E2EE alternative to Google Keep. Unfortunately it was slow to sync and its app was glitchy on my phone so I didn’t trial it for long.

And before you ask, I’ve never bothered with tools like Notion, Obsidian, Logseq, and their ilk. Those are all too complicated – they’re a “knowledge base”, a “workspace”, and other fancy descriptors like that – plus I feel paid apps like Notion will eventually go down the enshittification route, just like Evernote did. Notion is already touting itself as the “the AI workspace where teams and AI agents get more done together”. Ugh.

Happy days

To summarise, these are the tools I use:

Long, secure notes: Joplin (plus OneDrive for back-end storage and sync)

Short, casual notes: Google Keep

Kanban board: KanbanFlow

Shopping and other lists: Microsoft To Do

Bookmarks and read-later links: Pinboard

Passwords and TOTP: Bitwarden and Aegis Authenticator

Oh, and I use plain old text files (using Notepad++) for taking notes at work.

It’s taken me a while to get to where I am and I’m very happy with the set of tools I’ve settled on.

Do you have a primary note-taking tool? If so, what is it? I’d love to know.